Myth Busters

“Sthira sukham asanam”

That which is stable, that which is comfortable. That is asana.

“Heyam Duhkham Anagatam”

Pain in any form must be anticipated and avoided.

Sanskrit translated from Patanjali’s Yoga Sutras, an oral tradition estimated to be 5000-6000 years old and transcribed to the written word approximately 2400 years ago.

The YMCA, Spiritual Calisthenics, and Muscular Christianity were all established in Europe before the turn of the century. With the invention of machines during the industrial revolution an easier lifestyle was created and many people felt that man would fall into moral and physical decay. At the time of the British occupation, organizations such as the YMCA became established in India. The Indian yogis Krishnamacharya and Kuvalayanda, influenced by the western ideas of exercise and athleticism, established the health and fitness regime that dominates the yoga industry today. Yoga, as practiced today, is simply a product of that “physical culture” movement.

Mark Singleton’s book, “Yoga Body, The Origins of Modern Posture Practice,” illustrates that many modern yoga poses were created from a mix of western contortionism, military drills, and women’s gymnastics, combined with ancient yoga philosophy texts such as the Yoga Sutras and the Upanishads. Simply because yogis are shown doing these poses does not mean they are safe nor that they are anatomically correct for the human body. Yoga poses need to be bio-mechanically tested to establish their true value.

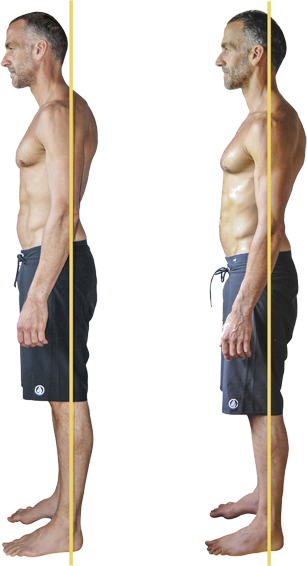

Tight abs become elongated stabilizers as shown in these before & after YogAlign photos

Back pain is caused not just by weakness, but also by excessive tightness in the anterior trunk muscles; thus over-contracting the abs is not a panacea for back pain, but rather a trigger for it. A tight six-pack in the abdominal muscles not only creates a tense ‘locked long back body’ but also can be dangerous to the health of the spine, nerves, organs and even emotions. Individuals with a six-pack may appear to be athletic and very fit, but could run into back problems as they age.

Common flexion exercises, like abdominal crunches, elbow-to-knee type sit-ups, and straight-leg forward bends continually contract the entire front of the body. This leads to a shortening of the anterior flexor chain and fascia connections that span from the skull to the top of the feet. Tense short abdominal muscles can load pressure on the discs in the spinal column, rotate the pelvis posteriorly, and compress the nerves exiting the spine. Tense abs pull the sternum (breastbone) towards the pubic bone, strain the back, and can inhibit breathing and movement.

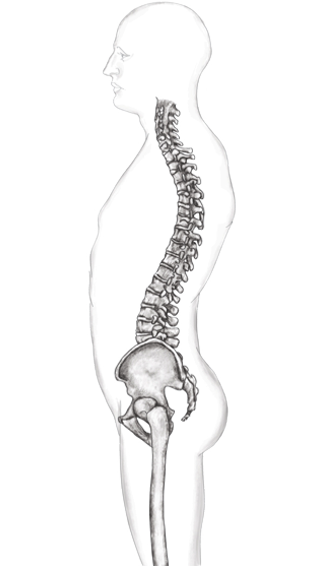

Staff pose is one of several yoga poses that require the body to form into a right angle. The human spine is designed with curves to provide shock absorption during movement and this requires a ‘necessary tension’ in the ligaments to keep the vertebrae ‘strung’ together. Positioning the body into a right angle flattens the spinal curves simulating the shape of a chair, the bane of our modern lifestyle. It does not make anatomical sense to exercise or stretch with the body in a right angle position such as staff pose and it is certainly not a functional way to sit.

Even if they feel ‘easy’ for those who are flexible, years of practicing right angle poses can stretch out the necessary tension in the sacral, knee and foot ligaments needed to keep these joints ‘sprung’ as shock absorbing structures. This leads to what I call the Sagging Sacrum Syndrome (SSS). With the lumbar region flattened and the sacrum sagging and flat, the breastbone goes down, the head goes forward, and the weight from the upper body compresses into the hip and knee joints.

Poses need to simulate how our body functions and moves in real life.

What is the sense in performing poses that go against nature’s design, having more to do with linear straight lines than our natural curving shape and bio-tensegrity design?

What is important when engaging the body is to direct our abs and trunk muscles to stabilize the spine, rather than to flex it. YogAlign® uses a breathing technique to draw the tip of the tailbone towards the pubic bone, requiring no external effort or force from the abdominal muscles.

Muscle tension is controlled by the nervous system; statically stretching and pulling on your hamstrings will not make them ‘longer.’ Toe touching can loosen ligaments and undo the necessary tensile forces that are needed to keep our body upright and our joints stable.

In order to relieve hypertension of the hamstrings we need to eliminate chronic tension and lengthen the front of the body and groin area so the hamstrings will not have to engage to balance against the forces of opposition. Once postural balance is achieved, the hamstrings will not feel tight and the urge to stretch and pull on the hamstrings will disappear.

Just watch a toddler bend over to pick up a beach toy and you will see how we are innately designed to move. Babies are excellent teachers, as they have not yet been stuffed in chairs and developed the dysfunctional posture habits that plague modern society.

Functional posture is dependent upon a spine that is in natural alignment and a body that is rooted in ease. In YogAlign®, natural posture and dynamic movement principles are utilized in every pose. Breathing practices that use the internal muscular forces of extension align our spine into optimal posture.

There are no straight lines in nature. Trying to flatten the back removes the inward curve of lumbar/sacral region. Over time, these body positions loosen ligaments allowing the sacral platform to flatten or tip backwards disappearing the natural 30-degree nutation angle needed for shock absorption during movement. After a period of years, many yoga practitioners begin to feel SI joint and low back pain. For some, this undermining of the main support system in the body- the curves of the spine – can compress and damage the hip joint and/or lead to the need for hip replacement.

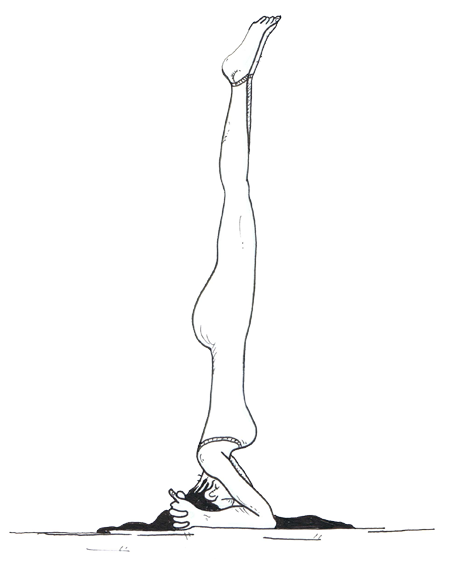

Standing on your head does not decompress the spine but instead compresses it in an inverted position. The delicate vertebral structure of the cervical spine (neck) is designed to carry only the weight of the head (5 -11 pounds), not the weight of the entire body.

Yoga teacher Patricia Sullivan wrote an account of the neck damage she suffered from her long-time practice of headstands. Her article, which was

published in the November 2010 issue of Yoga Journal, talks about the nerve damage she incurred by practicing “headstand” for 10 minutes a day, while ignoring all of the pain signals from her body cautioning her that the pose was not beneficial. Finally Patricia had a doctor examine her and they found “extensive damage including a reversed cervical curve, disk degeneration, and bony deposits that were partially blocking nerve outlets.” By her own admission, “my longing to excel both in my asana practice and as an asana teacher had led me to ignore my body’s signals and cries for relief.”